Crypto Art Annotations: From Cold Retromania to Creatively Weird

By Geert Lovink

When the “Homer Pepe” NFT sold for 205 ETH ($320,000),1 Barry Threw cheered: “The art world is a software problem now.”2 The choice of the young crypto-millionaires not to stash their profits away in investment funds or real estate is the most likely explanation for the non-fungible token (NFT) boom. In line with 1990s startup values, the newly acquired wealth should not be invested in fine art paintings or laudable charities, but continue to circulate inside the tech scene itself. The only aim of the virtual is to further expand the virtual: a boom that fuels the next boom. What else should one purchase after the Miami condo and the Lambo? It’s easy, épater les bourgeois: refuse to be patrons. Unlike colonial and carbon money, the Information-Technology (IT) rich are not interested in living forever and becoming esteemed supporters of avant-garde fine arts, architecture, or classical music. The surprising twist here is their sudden interest in digital arts.

money is a meme and now that memes are money we don't need money, we just need memes

— 4156 ⌐◨-◨ (@punk4156) August 3, 2021

We can define crypto art as rare digital artworks, published onto a blockchain, in the form of non-fungible tokens. Here, newly created speculative “assets”3 are financed with lavish amounts of “funny money,” superfluous cash that is spent on even more speculative ventures.4 Blockchain blogger David Gerard explains how the hype commonly known as web3 started: “Tell artists there’s a gusher of free money! They need to buy into crypto to get the gusher of free money. They become crypto advocates and make excuses for proof-of-work. Few artists really are making life-changing money from this! You probably won’t be one of them.”5 As author and journalist Brett Scott explains, crypto-hype promises artists they are destined for market greatness. But such hype, driven mostly by males, can only take off if everyone buys into it. “Far from saving you from bullshit jobs, trading is a bullshit job, and the only way to temporarily win at it is not to throw yourself into battle against ‘the market.’ It’s to collaborate in swarms.”6 The moment the hype takes off is the ultimate reward for the struggling pioneer. As writer Chelsea Summers quips: “There is nothing as sweet as professional vindication after years of people rejecting your work, underestimating your value, and generally dismissing you. And by you I mean me. And by professional vindication I mean money.”7

Take Hashmasks and CryptoPunks, fixed number storage places that make it easy to buy, sell, and compare similar images (“collectibles”). Here the speculative game is most obvious. The top ten images sold on CryptoPunks between the February and April 2021 hype period were priced between $1.46 and $7.57 million each, proving Mariana Mazzucato’s thesis in The Value of Everything (2018) that value had become subjective.8 It is telling that online details about the transactions fail to mention a description of the works, let alone their aesthetics, reducing the artworks to numbers such as #7804 or #3396. While “famous” NFT artworks may be handpicked by Sotheby’s experts, gallerists, critics, and curators, it is not (yet) clear where buyers can go to resell such works. Although the details are lacking, the overall logic is clear: artworks are stored value, that value is expected to rise, and these staggering prices will continue to be designated in fiat (government-issued) currency. While Bitcoin (BTC) or Ethereum (ETH) may rise and fall and the blockchain could vanish altogether, the scheme assumes this will never happen and that these “rare” digital artworks will keep their value.

Art History will be seen as before and after NFTs

— HANS (@Hans_2024) April 10, 2021

What is art at the crossroads of gaming, virtual reality, cryptocurrency, and social media? For some, there is an element of magic in buying a piece of “rare art.” For others, like musician Sybil Prentice, NFTs have a garage-sale vibe9: leftovers of an accelerated online life in which image production and consumption happen at a relentless pace. Yet, whether positive or negative, it’s clear that crypto art and non-fungible tokens alter the landscape of art. As Derek Edws and Stephen McKeon state, “in a natively digital medium, art takes on a more expansive role, intersecting with virtual worlds, decentralized finance, and the social experience.”10

Crypto Art

Crypto art is not just any image but comes with a distinct style, a particular aesthetic that goes with the territory. The common cultural references here are not New York’s Artforum or Berlin’s Texte zur Kunst but the online pop culture of imageboards: memes, anime, Pokémon cards, and the like. Jerry Saltz stated:

Most NFT so far is either Warhol Pop-y; Surrealism redux; animated cartoon-y; faux-Japanese Anime; boring Ab-Ex abstraction; logo swirling around commercial; cute/scary giff; glitzy screensaver; late Neo-conceptual NFT about NFT-ism. All Of those are NFT Zombie Formalism. D.O.A.

— Jerry Saltz (@jerrysaltz) April 5, 2021

In short, what’s striking is the overall retrograde style, as if we’re stuck in a loop, forever repeating Groundhog Day. The settings are copy-pasted from American science fiction films and comic books and projected into today’s games environment.

NFTs are based on the assumption that scarcity is a good thing that needs to be reintroduced. Scarcity creates the possibility of skyrocketing value and speculation, which may, in turn, attract investors. The fatal destiny of the artwork is to become unique. Ours is an anti-Benjaminian moment when digital art in the age of technical reproduction makes its big leap back into the eighteenth century. At the same time, we need to remind ourselves that “decentralized finance” is an alternative reality, driven by libertarian principles, fed by a temporary abundance of specific free money and a religious belief in technology that will save humankind. Digital reproduction and “piracy” are no longer the default. Those who disagree with this premise would need to become hackers (again), cracking the code in order to enjoy the artwork. Is this the only way of making a living, to become “rare” again?

I contacted @lunar_mining because of a critical (since deleted) tweet: “NFTs =! digital art. NFTs replicate the mechanics of the art marketplace, but I’ve yet to see an NFT with meaning or soul or abyssal depth. There’s an emptiness to NFT trading, a nihilism: it is a marketplace without ideas.” The person behind this statement is the artist and former CoinDesk editor Rachel-Rose O’Leary. I asked her opinion about crypto art: “There’s a low-level boyish signaling out there but also some nuance that is emerging. For example, you can see the early stages of meme culture fusing with collectibles, which is potentially a powerful combination.” For O’Leary, art ended with Sol LeWitt, who said that the idea becomes the machine that makes the art. This realization contains the key to art’s exit from itself. Crypto is an idea turned into a machine. It is the crystallization of ideas into architecture. By binding narrative to a machine, crypto has the potential not simply to describe the world but to actively shape reality. “In a world of unprecedented political urgency, contemporary art has retreated into subjective delusions. In contrast, crypto offers a powerful regenerative vision. That’s why I’m expending my energy here rather than the art world.” She observes a hollowing out of culture in general. “Art on the art market shares the same overpriced, pop-culture feel as the current NFT market, related to a declining culture industry and the behavior of markets than NFTs or crypto culture itself.”

In this light, NFT platforms aren't competing with the auction house or gallery--they're competing with Patreon. (end, I think)

— Tina Rivers Ryan (@TinaRiversRyan) March 24, 2021

Is the essence of art that it should appeal to (crypto)investors? Are these patrons the medieval cardinals of today? Here we see how the perverse logic of the art market can become internalized in the mind of the artist. According to Robert Saint Rich (in a since deleted tweet), “the influence of social media has created a perspective in artists that they need to produce masterful quality works in a large enough quantity so that they can be shared on an almost daily basis. This is an impossible standard that forces artists to create uninspired work.”

Artists create banal artwork for banal tastes, hoping to give their pieces popular appeal. But paradoxically, the aim of investors was never to collect art pieces. The crypto art system is a financial system, putting creators into peer-to-peer contact with the nouveau riche of today: the crypto-millionaires. While we may critique this situation, it cannot be undone. A return to “normal” is no longer in the cards. This is a digital world; we’ve passed the point of “newness.” Crypto art belongs to that moment in the history of contemporary art when both painting and conceptual art forms are becoming impossible.

Where’s the Art?

Let’s define what we encounter here as “admin art” that solely exists on a ledger. These are meta-tagged images defined by their desire to become a record, to obtain a timestamp, to embody a digital unit of value. The value is inscribed inside the work, readable by machines. Crypto art is retrograde in that it wants to put the genie back in the bottle and create digital originals. Its innovation claims to fix past structural mistakes. What it shares with the avant-garde is its initial unacceptability. The discontent of crypto arts lies in the perverse obsession to get onto the ledger.

Admin art is what art becomes when it is defined by geeks. These geeks dress up as notaries and play-act at being lawyers, fastidiously policing “authenticity records.” At the center of all, this is the notion of ownership and the promise of being “securely stored on the blockchain.”11 How is an artwork purchased and ownership transferred? First you need to set up a digital wallet on a smartphone and purchase some cryptocurrency (Ethereum in the case of crypto art). Then visit a website with the art pieces. The interface is structured in typical fashion, with “top sellers” and “top buyers” conforming to the established “most viewed” influencer logic. We then have recently added works, followed by a section where you can “explore” the cheapest or highest priced NFTs. As is the case with any platform these days, the user design is profile-centric. It is only after you have created a profile that you are able to purchase and “mint” an artwork. Either there will be an instant sale price or one set by an auction.

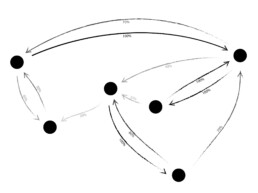

Ownership of this virtual object depends on a chain of institutions or intermediaries, a dependency that is right in your face yet somehow remains undiscussed. The most obvious, of course, is your connectivity to the internet. But alongside this, there is a stack of necessities, from cloud services to browsers, operating systems, the Ethereum currency, the blockchain, the wallet, and platforms like OpenSea and Foundation, each with its own layers of services, networks, and transaction fees. So where exactly, in this soup of platforms and protocols, is the token ID?

If the production and distribution costs of digital artworks tend toward zero, what does it feel like to produce worthless works? What are the mental costs, the “creative deficit” if one can freely copy-paste, steal motifs, and quote without consequences? While some celebrate the infinite amount of possible combinations, others lament the culture of indifference this entails. This culture is driven by the promise of opportunity, the excitement of being in on the game, on the payment train. Instead of underground aesthetics that need to be experienced firsthand, the focus of the artistic endeavor has shifted to storing value.

So the excitement for crypto art is fed by an unspoken desire to disrupt the old Silicon Valley order and its outdated obsession with free things and free ideas. However, what remains is the central role of the market, which is run by a handful of platforms and managed by curators. Jargon like “hotbids” and “drops” seem to come from nowhere. This is by no means a move away from post-digital art (or post-internet art values, for that matter). Crypto art is material as hell. It cannot exist outside of data centers, undersea cables, servers, wallets and the handheld devices of its traders. A substantial number of crypto artists draw on paper. The maker’s ideology and practice is never far away.

In the debates, NFTs claim to be possible sources of income that fight mass precarity amongst artists and creative workers. Selling crypto art as unique works (or in limited series) is claimed to be an additional income stream for most producers. The demand for a universal basic income will remain in place though. High-flying artist Beeple is the exception to the rule. Overinflated prices merely say something about the Tulipomania state of crypto; the wealthy that need to stash their money somewhere. Marketplaces for crypto art are, all too often, ways to temporarily store “funny money” elsewhere. What’s prevented at all times is a sustainable financial solution. The ideology of speculative cryptocurrency hoarding12 and the demand of artists for a living wage are inherently incompatible.

Art of the Flip

The investor does not care about the artwork itself. NFTs are bought with the sole purpose to resell them. Investors track the growth of the artist’s net worth, hoping to receive royalties each time a work flips. The difference from the traditional art market is that there are fewer intermediaries and gatekeepers; fewer curators, critics, galleries, biennales, museums, and auction houses. The market for crypto art is internalized and explicit. All romantic notions have been eliminated, replaced by a tightly integrated sales chain. According to curator and critic Domenico Quaranta, the NFT craze has been guided by the “investment of wealthy crypto owners who wanted to demonstrate how certified digital scarcity can be crafted on the blockchain, and wanted to attract new crowds of creators and investors in the field; and the interested investment of auction houses, who wanted to open up a new market and attract huge amounts of cryptocurrency that could only be invested, so far, in other cryptocurrency and that can now be used to buy art and promote oneself as a visionary patron.”13

The startup logic here is one that benefits early adopters, one not dissimilar from insider trading and similar venture capital tricks. As Quaranta states, “The lucky ones are those who have been part of the crypto community for quite a while, who bought Ether when it was cheaper, who have connections in the field that are open to support them, bidding to launch the auction or to raise their quotations. This is why the NFT market has been often explained as a Ponzi scheme, where new investors are attracted – with promises that remain mostly unfulfilled – into the game in order to generate revenues for the early investors.” However, Quaranta’s conclusion resonates: “Refusing to engage would probably be a bad choice, also considering the fact that this environment is very likely to be a test ground or a first prototype of what the internet would be, like it or not. Choosing the right mode to engage is key.”

Geraldine Juarez expresses disgust about NFTs and why she is not interested in “technologies that leave people behind and make everything more difficult for everyone.” She’s tired of the “creepto” art scene’s refusal to take things for what they actually are. NFT art would increase social inequality because it engages with a form of “financialized capitalism that emphasizes investment as a ‘political technology’ concerned with speculation more than with commodification.” Digital artists, “situated at the bottom of the art market pyramid . . . are the lucky marginal customer selected by crypto-finance to justify the normalization of blockchain technologies and the deployment of the casino layer of the web.”14 Net art is under pressure from all sides. Is this why so many digital artists willingly allow their work to be reduced to an “asset”?

From Cold Retromania to Creatively Weird

Ledger technologies are, at their core, boring, administrative procedures. There is no artistic potential in them, other than the “art and money” engagement described by Max Haiven in Art after Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization (2018), which plays around with concepts such as the gift, exchange value, and symbolic exchange. The blockchain is, in essence, a follow-up to the excel sheet. There’s no Excel Art – and for that, the world can be thankful. We suffer enough from the bookkeeper logic.

How many millions have been killed as a result of some cold spreadsheet calculation? This is a question that, surprisingly, can unite the contemporary and crypto art worlds. The opportunity here is to be able to ignore, personally and collectively, the harsh selection mechanisms that are required in the first place. Without a rigid, closed, and interconnected culture of critics, curators, gallery owners, and museum directors, the real speculation cannot take off.

We should challenge the genre to become even more weird in a contemporary fashion and seek a dialogue with today’s alienated condition of the platform billions. Crypto art is marked by an unreconstructed desire to return to a revolutionary period, before Thatcher and Reagan, when psychedelics were still possible doors of perception to overcome the narrow boundaries of the narcissistic Self. Rather than awarding this retromania, we should instead begin a fundamental makeover of the crypto-social imagination, one aimed at confronting our messy present. It’s easier to drift off and time travel back to Ancient Mesa, Russalka, or Jakku than it is to radically rethink contemporary places such as Niamey, Karachi, or Osaka. It is lazy to define your basic aesthetics on work done by others. But there are also other ways of seeing.

During the pandemic’s quarantines and lockdowns, countless hours were spent online. If crypto art has not benefited from that booming “attention economy,” when will it? In order to make full use of the current situation, digital art needs to open up to a multiplicity of genres, schools, currents, and aesthetics, and give them a distinct twist. Pull the virtual game worlds into our dusty urban wastelands and create real hybrids, not 2070 escape worlds. If crypto is so big and “disruptive,” it should easily be able to shrug off the aesthetics of the past and create its own distinct style and visual language. Tell us how we should do crypto performances, dances, and dress-up. Create an entirely singular style. It’s not hard to leave behind the Pokémon card collectors. We can do it.

Critics should be careful to repeat the obviously useless nature of the blockchain and instead attempt to understand the collective fascination with it. The irrational forces that drive the crypto bandwagon are not to be lightly pushed aside with “rational” liberal arguments. Crypto may soon become a dominant twenty-first-century form of administration. To effectively oppose it, we need a radical software theory that is able to go to the core of this technology. Refusal and resistance should be based on autonomous intelligence gathering, not empty gestures.

Geert Lovink is a Dutch media theorist, internet critic, and author of many books including Zero Comments (2007), Networks Without a Cause (2012), Social Media Abyss (2016), Organization after Social Media (with Ned Rossiter, 2018), Sad by Design (2019), and Stuck on the Platform (2022). In 2004, he started as a Research Professor (Lector) at the Amsterdam University of Applied Science (HvA), where he founded the Institute of Network Cultures. In late 2021 he was appointed Art and Network Cultures Chair in the Art History Department, University of Amsterdam.

> https://networkcultures.org/

Beyond Follows

by Sarah Friend

Imaginary Blockscape

by Felix Linsmeier